January 2, 2024

I’f you’re like me, you may have had mixed feelings in the past few weeks about the imminent arrival of 2024. With controversial wars raging and a shocking appetite for autocracy growing around the globe, plus a divisive, ultra-important election season ahead here at home, I find it a bit hard to concentrate on other matters, including cabaret matters. Some tough questions arise.

What significance does what we do in the so-called cabaret community have when so much around us seems to be a shambles? Is cabaret essentially a frivolous art? Or does it somehow give us a voice for change that is stronger than we’d assumed?

There are no simple answers. In order to preserve hope, I wish everyone a happy new year, cross my fingers, and hope for the best. There are good people in the world. Smart people. Energetic people who do their best. That’s a good sign. Right? Maybe it’s like the lyric our ears have probably caught at some point in these past few weeks: “From now on, we’ll have to muddle through somehow.”

Thinking about all this, I decided for some reason to have look at a book that’s been sitting neglected on my shelf for a long time. Called simply The Cabaret, it’s the work of Polish-born scholar and novelist Lisa Appignanesi. It was first published by Yale University Press in 1975, then revised and expanded in 2004.

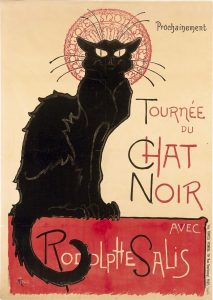

Appignanesi traces cabaret back to 1881 Paris and the opening of a celebrated club in Montmartre called Le Chat Noir (The Black Cat), where poverty-plagued social outcasts—writers, artists, and members of the “criminal class”—congregated. They’d hang out, drink, and be human together, and then they’d ridicule bourgeois values together. Part of the appeal was that writers would perform their own material. Sometimes things got pretty noisy, and disgruntled outsiders would complain or even intrude on the festivities. (Le Chat Noir was not classic Oak Room at the Algonquin, but it sure sounds lively.)

The years passed, and cabaret spread throughout most corners of Europe and beyond. Some wonderful characters figure in the pages of The Cabaret, and many of them happened to make their mark in troubled twentieth-century Germany.

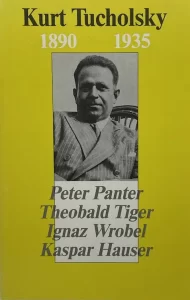

There was Marya Delvard—“the first vamp of the [20th] century”—who electrified Munich in 1901 singing the song of a proud whore, ready to accept her fate of an early death. Also Kurt Tucholsky, a “little fat Berliner,” who became a prolific satirist in the 1920s, stubbornly warning Germany of the madness that lay ahead. Or the flamboyant Valeska Gert, whose specialty was “socio-critical dance pantomime.” (She once supposedly asked Bertolt Brecht to define what he meant by “epic theatre,” only to receive the reply, “What you do.”)

Appignanesi also writes of later performers whose names we’re much more familiar with: Marlene Dietrich, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce. (Interestingly, she finds the attitudes of traditional cabaret lingering inside the doors of 21st century stand-up-comedy clubs.)

What stood out to me in this lavishly illustrated book is not only the devotion to causes of justice and liberty shown by the artists Appignanesi spotlights, but also the stinging sense of futility they faced. “I write and write—and what effect does it have on the conduct of my country?” Tucholsky wondered. And with the rise of the Third Reich, simple stinging futility became a pain seemingly too inconsequential (and too widespread) to mention.

Look at this struggle from one angle and it’s beyond depressing. But squinting in a different way, you can see some inspiring instances of valor. We can learn some things from these cabaret fore-parents of ours

I don’t think performers need to give up their planned tributes to Tommy Steele or Vicki Carr and instead spend all their efforts in 2024 on saving our republic from autocratic madmen. No, go on with the shows! We need them.

And, of course, there’s no specific political sensibility—no universal set of assumptions that everyone in the world of cabaret shares.

Still, I personally look forward to shows like some I’ve seen in the last few years—such as Stephen Hanks’s “Ride the Blue Wave” fund-raising evenings and Joe Keenan’s Everybody Rise: A Resistance Cabaret. And I hope we’ll all continue to offer moral (and maybe more-tangible) support to the drag and trans performers among us, both locally and throughout the country—fellow artists who have been singled out in our time for unwarranted censorship.

There seems still to exist in contemporary cabaret plenty of that spirit of community, maybe hailing all the way back to Le Chat Noir days. Speaking (or singing) truth to power in unison with others can be empowering, even in a room with only a handful of listeners.

In her coverage of a Russian club called Stray Dog Cabaret, which opened in 1911, Appignanesi quotes a lyric from what she refers to as “cabaret’s own hymn”:

In the cellar, there’s a shelter,

Everyone who goes is a stray.

There’s no melancholy here,

And no fleas.

We glorify the world with our barking.

So: Happy 2024, everyone! Here’s to less muddling through—and to more glorious barking, especially the kind with a bite.

Bits and Pieces

As we move into 2024, here are a few items from 2023 that didn’t quite fit into previous columns:

At a release party at Don’t Tell Mama for her first-ever album, Wait ’Til You See What’s Next, Linda Kahn performed several songs from that recent release, then treated her listeners to a pizza party. Although this was not a holiday event, some timely Christmas imagery emerged in one of the selections Kahn performed, a song by Christopher Denny, who plays the number on the album and also played it for the singer at DTM. “Anywhere with You” is a charming number with an engaging melody and lyrics about October in Paris and Christmastime in New York. It deserves to be better known in cabaret circles and perhaps now will be.) Denny accompanied Kahn on some numbers at this mini-set, and the CD’s proud producer, David Friedman, took to the keys on others. Jeff Harnar directed. In the house was Julie Gold, who wrote “The Journey,” another of the album’s songs that Kahn sang at the event. (11.28)

// //

A rollicking holiday benefit show for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, hosted by Goldie Dver (in spirited Dolly Levi mode), arrived at Don’t Tell Mama early in December. The Season: Straight Up with a Twist featured an array of secular Christmas songs (titles celebrating Santa, elves, and snow, with Baby JC pretty much MIA), plus Stephen Schwartz and Steve Young’s “The Chanukah Song.” Also included were selections that aren’t holiday numbers at all but certainly qualified as songs of good cheer. Among my favorite performances: Aaron Lee Battle’s stirring “Feeling Good” (Bricusse and Newley), Tanya Moberly’s dexterous turn with the late Rick Jensen’s tricky “You’d Better Say Yes,” and Lennie Watts’s soulful “Celebrate Me Home” (Bob James, Kenneth Clark Loggins). After a raffle to raise even more money for St. Jude, it was St. Nick (the convincing Michael L. Walters) who closed down the boisterous party, leading everybody through a chorus or two of Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas.”

Goldie Dver reports that the show, raffle, and related efforts raised well over $2,000 for St. Jude (12.3).

// //

Bob Ader opened a window on yesteryear with Harry Who? (The Songs of Harry Warren) at Don’t Tell Mama (directed by Marilyn Spanier). Ader—perplexed by all the people who should know who composer Harry Warren was, but don’t—began his show not with a song but with the pep talk that Warner Baxter’s character gives to Ruby Keeler’s in the 1933 Warner Bros. film 42nd Street, culminating with the still-resounding command: “Sawyer, think of Broadway, dammit!”

That done, Ader launched into a medley of the film’s title song and the slightly later-written “Lullaby of Broadway” (which won Warren the first of three “Best Song” Oscars). Very much a performer from the Old School (I could almost smell the vintage chalk dust), Ader presented the songs pretty much as they would have been performed when they were new, his voice deep, assured, and resonant. Along the way, he tap-danced repeatedly (and energetically) right there on the itsy Brick Room stage; delivered some quips; impersonated Al Jolson, Cary Grant, and Groucho Marx; and provided some fun facts about his rather reclusive subject. He explained, for instance, how Warren used a snippet of fanfare heard at a racetrack when he fashioned the opening line of the Oscar winning “You’ll Never Know.” (Ader also revealed that he himself worked with Judy Garland in 1967. That raised some audience murmurs!) I enjoyed his direct and unpretentious approach, as well as the glowing smile on the face of his pianist, Elliot Finkle, as his fingers embellished melodies from a composer that he, like Ader, seems to revere. (12.11)